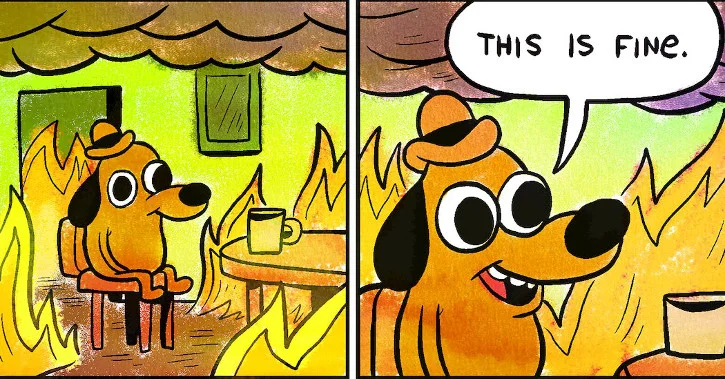

K.C. Green, Gunshow comic #648, January 9th, 2013

The kindling was already everywhere

There are no easy answers. More important, there are no purely digital answers.

…We didn’t get where we are simply because of digital technologies. The Russian government may have used online platforms to remotely meddle in US elections, but Russia did not create the conditions of social distrust, weak institutions, and detached elites that made the US vulnerable to that kind of meddling.

…Russia did not make the US (and its allies) initiate and then terribly mishandle a major war in the Middle East, the after-effects of which—among them the current refugee crisis—are still wreaking havoc, and for which practically nobody has been held responsible. Russia did not create the 2008 financial collapse: that happened through corrupt practices that greatly enriched financial institutions, after which all the culpable parties walked away unscathed, often even richer, while millions of Americans lost their jobs and were unable to replace them with equally good ones.

Russia did not instigate the moves that have reduced Americans’ trust in health authorities, environmental agencies, and other regulators. Russia did not create the revolving door between Congress and the lobbying firms that employ ex-politicians at handsome salaries. Russia did not defund higher education in the United States. Russia did not create the global network of tax havens in which big corporations and the rich can pile up enormous wealth while basic government services get cut.

…If digital connectivity provided the spark, it ignited because the kindling was already everywhere.

Americans just want a shortcut

We may be missing F. Scott Fitzgerald’s real message when he wrote, “There are no second acts in American lives.” Maybe he wasn’t saying that we can never recover from early failures.

In a 2010 column in The Atlantic, writer Hampton Stevens pointed out that Fitzgerald wrote for the theater at Princeton and later Broadway (and Hollywood). “With ‘no second acts,’ he was almost certainly referring to a traditional, three-act drama, in which Act I establishes the major conflict, Act II introduces complications, and Act III is for the climax and resolution.”

Fitzgerald may have been saying that, as Americans, we grasp for premature resolutions, impatient with complications along the way. During the second act, the protagonist is unable to resolve the complications because they don’t have the right tools yet. Our lead character must grapple against the odds—often paying a big price along the way. But Americans? Usually, we just want a shortcut.

The world of action

So how do we, in the scientific world, begin a dialogue with the world of action?

The world of action.

For a room of scientists who prided themselves as belonging to a specialized guild of monkish austerity, this was a startling provocation.

“Few of these policy geniuses were showing much sense. They understood what was at stake, but they hadn’t taken it to heart. They remained cool, detached — pragmatists overmatched by a problem that had no pragmatic resolution. ”

They never got to the second paragraph

Most everybody else seemed content to sit around.

When the group reconvened after breakfast, they immediately became stuck on a sentence in their prefatory paragraph declaring that climatic changes were “likely to occur.”

“Will occur,” proposed Laurmann, the Stanford engineer.

“What about the words: highly likely to occur?” Scoville asked.

“Almost sure,” said David Rose, the nuclear engineer from M.I.T.

“Almost surely,” another said.

“Changes of an undetermined — ”

“Changes as yet of a little-understood nature?”

“Highly or extremely likely to occur,” Pomerance said.

“Almost surely to occur?”

“No,” Pomerance said.

“I would like to make one statement,” said Annemarie Crocetti, a public-health scholar who sat on the National Commission on Air Quality and had barely spoken all week. “I have noticed that very often when we as scientists are cautious in our statements, everybody else misses the point, because they don’t understand our qualifications.”

These two dozen experts, who agreed on the major points and had made a commitment to Congress, could not draft a single paragraph. Hours passed in a hell of fruitless negotiation, self-defeating proposals and impulsive speechifying. Pomerance and Scoville pushed to include a statement calling for the United States to “sharply accelerate international dialogue,” but they were sunk by objections and caveats.

They never got to policy proposals. They never got to the second paragraph. The final statement was signed by only the moderator, who phrased it more weakly than the declaration calling for the workshop in the first place.

“The first suggestion to Rafe Pomerance that humankind was destroying the conditions necessary for its own survival came on Page 66 of the government publication EPA-600/7-78-019.”

The year was 1979. Rafe Pomerance, trained as a historian, was the deputy legislative director of Friends of the Earth, and this moment marked the beginning of a political and scientific effort that tragically, almost, saved the world.

The quote continues,

Pomerance paused, startled, over the orphaned paragraph. It seemed to have come out of nowhere. He reread it. It made no sense to him.

He proceeded as a historian might: cautiously, scrutinizing the source material, reading between the lines. When that failed, he made phone calls, often to the authors of the reports, who tended to be surprised to hear from him. Scientists, he had found, were not in the habit of fielding questions from political lobbyists. They were not in the habit of thinking about politics.