Not the universe.

The passage of time is not for us a rational thing to contemplate. It’s something we live into — we are the passage of time. We are this constant computing of time.

We can think about reality without space. We can think about reality without things. But it’s very hard to think yourself in a reality without time. You wouldn’t know how to start thinking.

But the confusion is: is this because reality by itself cannot be thought of without time?

No, it is because our thinking cannot be thought without time. We cannot think without time. We are a time machine. Not the universe.

The one minute

BARKEEPER

Will you go looking for her?

THOMAS

She is in the past.

…The past is not my concern.

And the future is no longer my concern either.

BARKEEPER

What is your concern, Tommy?

THOMAS

The one minute.

The soldiers minute.

In a battle that’s all you get.

One minute of everything at once.

And anything before is nothing.

Everything after, nothing.

Nothing in comparison in that one minute.

“Once certain realities of the physical world are brought into play their effects are essentially permanent, regardless of whether or not we have a spiritual awakening.”

Long-term backwards vision

The big stuff can never get done

Now the war

Kennicott's essay, in reaction to this week's mass shootings in El Paso and Dayton, begins with a reflection on a photograph by Joel Angel Juarez of police in paramilitary gear outside a Hooter’s restaurant in El Paso.

Kennicott continues,

This convergence of our commercial landscape with violence is what the 21st century, slow-motion but persistent American war looks like. It also looks like the underside of a child’s school desk, people hiding in closets and wailing into cellphones, SWAT teams in parking lots, nightclubs with overturned bar stools and tables, piles of shoes abandoned outside a bar, and movie theaters soaked in gore. If we have the courage to do what we must do and look at the facts, we will also see that in one essential way, the American war looks like every other war everywhere on the planet, full of bodies riddled with bullets, bloodied, broken and dead.

Some wars are over in a day, or a week, and others go on for years. If there are opportunists and profiteers and cynical actors who are willing to fuel the mayhem for a tiny bit of personal or political advantage, then they can go on for decades. If war takes root in a society slowly, or by stealth, it can come to seem the ordinary state of affairs.

“And that was the problem with 1968. People went ahead and built those things without worrying much about the consequences, because they figured that, by 2018, we’d have come up with all the answers.”

“[By 2018] the transmission of pictures and texts and the distant manipulation of computers and other machines will be added to the transmission of the human voice on a scale that will eventually approach the universality of telephony. What all this will do to the world I cannot guess. It seems bound to affect us all.”

“It’s not easy to persuade citizens of a democracy to accept real financial sacrifice in the here and now for the sake of a diffuse benefit in the future.”

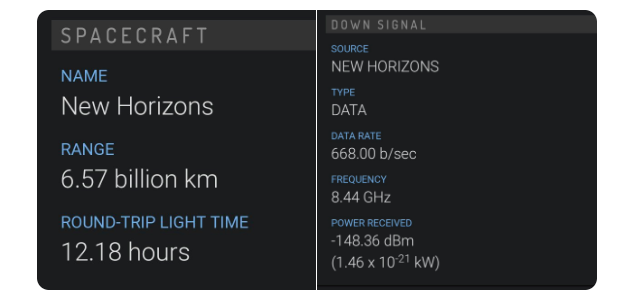

“Talking to the Kuiper belt is like talking to an Ent, from the other side of the forest.”

It takes decades

Speed

Everything nowadays is ultra

A shadow of what they once were

“Humans are mainly a temporary container for their genes”

In context,

…A small window in which to act

“The excruciating power of Zweig’s memoir lies in the pain of looking back and seeing that there was a small window in which it was possible to act, and then discovering how suddenly and irrevocably that window can be slammed shut.”

“Smart people are beginning to understand the size of the problem, but they haven’t yet figured out the timing; they haven’t yet figured out that the latest science shows that this wave is already breaking over our heads.”

“The true debate lies in the solutions and in mobilizing the social and political will to act upon our knowledge. Deciding not to act is a choice itself, and one that we cannot correct later. The time to act is always now. Because the longer we wait, the worse the outcomes will be.”

“If we had started 20 years ago…such a plan might have made sense.”

“Smart people are beginning to understand the size of the problem, but they haven’t yet figured out the timing; they haven’t yet figured out that the latest science shows that this wave is already breaking over our heads.”